The Conspiracy Theory of Wilt Chamberlain and the “Presentism” Trap

The Conspiracy Theory of Wilt Chamberlain and the “Presentism” Trap.

How to interpret the hysterical rumors that his record of 100 points in a single game is untrue?

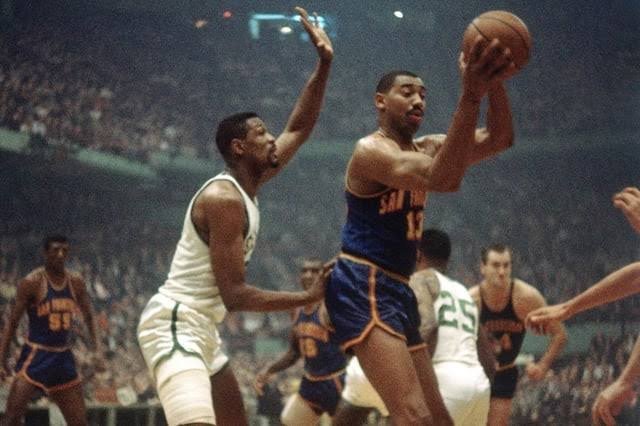

The NBA record for most points in a game is still held by the late basketball great Wilt Chamberlain, who scored 100 points against the New York Knicks on March 2, 1962. The mark has stood for more than 60 years. That’s 19 more points in a single night than second-place player Kobe Bryant has ever had. It surpasses the record single-game score set by Michael Jordan by 31 and the career high scores of LeBron James and Shaquille O’Neal by 39. Additionally, O’Neal, James, Bryant, and Jordan each had a three-point line.

One by one, Chamberlain counted his points.Even though it’s a simple statistic to verify—just check the box score!—some people on sports social media don’t think it happened. They claim that the NBA staged the 100-point game as a PR stunt. Although this conspiracy idea has been around for a while, it appears to be making a comeback lately.

Paul Farhi of the Athletic states, “The skeptics populate TikTok, YouTube, Reddit, Facebook and X/Twitter with videos and posts.” Googling phrases like “Wilt Chamberlain hoax” or “Was the 100 point game faked?” will lead you to unbelievable places.

Even while the idea of 100-point-game trutherism seems absurd, it merits discussion because it stems from a presentism that is all too pervasive in other spheres of our public discourse—applying today’s attitudes, assumptions, and expectations to the past.

Watch those conspiracy theory videos, and you’ll see skeptics citing a litany of issues that don’t make sense to the average current viewer. The fact that there is no visual trace of the game remaining is by far the most frequent criticism. If there is no game tape, there may not have been a game at all. When Pat McAfee of ESPN podcasts discovered last year that there was no footage available for the game, he became concerned. “That certainly sounds like something from the past,” said one sportswriter who “used to to simply make things up,” McAfee remarked. “That was the first time I heard there was no video of this, and it’s difficult not to assume the worst in 2023 [when] there is no video of anything.”

Although McAfee acknowledged the existence of an audio clip from the game as proof, it is not an entire radio station broadcast, which made one of his cohosts believe it to be a hoax. A college student, listening to a rerun of the fourth quarter early the next morning, recorded the game using an outdated tape recorder. Raising questions, the tape was only made public in 1988. Additionally, one of the announcers gave two different scores: 169–150 and 169–146. Officially, the score was 169–147.

Truthers mention a number of more apparent anomalies. About 4,000 people attended the game, which was held in remote Hershey, Pennsylvania, rather than in Philadelphia or New York.

The fact that professional basketball was not the dominant sport in the sports media in 1962 explains almost all of the red flags, aside from the broadcaster’s misrepresentations of the score, a discrepancy that is well-known to historians who have examined original documents in almost any field. A match between the playoff-bound Warriors and the bottom-dwelling Knicks in early March wasn’t exactly must-see TV, especially with Rawhide and The Flintstones on. As Farhi points out, many NBA games were never broadcast on television. The Knicks did not broadcast their road games, but the Warriors did. There were no national media partnerships, and terabytes, not a warehouse full of reel after reel, would have been needed to archive audio and video recordings.

The reason the game was held in Hershey is that NBA owners, who were keen to expand the game outside of their towns, frequently toured their events, much like the NFL currently does with games in Europe. Regarding the mere 4,000 attendees: well, it was an NBA game. Oh well. Instead, why not watch Fred and Barney at home?

Take advantage of our exclusive, in-house coverage of ideas, culture, and the arts by becoming a paid or free Bulwark subscriber.

I find that the fate of the game ball is the most telling example of how 1962 and today differ from each other.

After the game, Kerry Ryman, an adolescent, stole it from Chamberlain and ran out of the building while the cops chased after him. I take it he wanted to sell it? No. The child’s guardians attempted to return it to Chamberlain and the Warriors. They showed no interest. Ryman experimented with it. Outside. until the end of it.

He didn’t auction it until 2000, when sports memorabilia started to gain popularity, and it brought in slightly more than $67,000. That is very different from Major League Baseball creating customized baseballs with invisible marks for Aaron Judge’s 2022 home run record attempt to surpass Roger Maris’s record. The league required verification of the record-breaking ball. At auction, it brought $1.5 million.

It’s simple to write off the commotion around the 100-point game on the internet as the actions of random internet users. However, the argument for conspiracy, as it now, is based on the rejection of a fundamental finding of historical research: that the past is a distinct historical setting populated by individuals whose presumptions diverge from our own in significant and often subtle ways.

It’s easy to find fault with the conventional explanation of Chamberlain’s game if one does not recognize the importance of change over time. NBA games are now regularly televised and recorded. Sure, there are some differences in the regulations, but this is the NBA, a multibillion dollar worldwide brand. I mean, that’s how it has to have always been?

Wilt Chamberlain had to have been equally well-known if he was the LeBron James of his day. “Although it’s early in the NBA’s history and the sport wasn’t as popular in 1962 as it is now,” a YouTuber remarks, “it raises so many red flags for me to not have a televised version of this game or video of this game.” But it’s merely a warning sign for a 2024 mindset.

All of us have a tendency to be present. I’m 44 years old, and lately I have to try hard to recall how airport pickups operated before cell phones. When the individual being picked up was ready, how did people know? Extracted from behind layers upon layers of my personal experience.

More serious examples are easy to find once you start looking. Political debates that invoke history tend to overemphasize ways in which the present is like the past and ignore the many ways in which the past was very different.

For example, I think the Founding Fathers have a lot of wisdom to share. But I also understand their words can only be helpful up to a point because their habits of mind were shaped by their time, and the context in which they spoke, wrote, and acted was in important respects very different from ours. That doesn’t mean twenty-first people are always enlightened and eighteenth-century people were always backwards and benighted. That error is just another manifestation of presentism. My point is just that the pastness of the past is something to wrestle with as we make decisions today.

The only approach to comprehend how the past can—and cannot—inform the present is to study history. Regretfully, there are fewer people studying history at all these days.

Too frequently in grades K–12, math, reading, and standardized reading and math tests take precedence over history. The study of premodern history feels like a dying breed as universities place an increasing emphasis on students’ preparation for the workforce. Instead, the field is concentrating its efforts on modern history and its connections to current events. James Sweet, the American History Association’s president at the time, attempted to alert colleagues in 2022 to the risk of presentism in the growing practice of writing history with current politics at the forefront. Sweet stated, “This new history frequently ignores.

Post Comment